Making Do

It became apparent to Edgar that he had taken on rather more than it was reasonable to try and accomplish single-handed.

He scanned the newspaper to see if he could afford an assistant. Quite by chance, Geoffrey Mackenzie-Ferguson was advertising for a job as a farm assistant. He was an Englishman the same age as Edgar.

Ferguson arrived on the farm in the latter part of the dry season and immediately took an immense liking to Witchwood. They would divide the work between them. Ferguson was a first-class motor mechanic, and would save them heavy garage bills by doing all routine jobs on the car like decarbonizing. He was also a first-class carpenter which would prove to be of immense value in the finishing of the house. But he had no special interest in cattle or poultry, and therefore Edgar took sole responsibility for the livestock; it was altogether a most satisfactory symbiotic relationship.

The house was not yet habitable. Edgar had abandoned tent living and built two rondavels for himself. They decided to share a sleeping hut and furnish the living hut really comfortably, so that, with easy armchairs and a proper dining room table, they could have somewhere to live a partially civilized life.

Still these living quarters had severe disadvantages. Pyjamas and sheets were always damp during the rainy season. In the winter on exceptionally cold nights in June till August the only means of heating the thatched huts was with a paraffin stove. They went to bed early simply to keep warm. Flit spray did not deter ants of all shapes and sizes making their way into the hut.

After a spell of bad weather it was necessary to put all furniture, clothing and bedding out of doors on the first sunny day because all fabrics accumulated blue mold and even furniture began to show traces of mildew.

Edgar was adamant that their living expenses not eat too deeply into their capital. There was no question of being short of food, because having a herd of cattle and a flock of poultry, they had plenty of milk, eggs and fowls for the table but there were no frills. They both liked bacon, and decided they could afford it one day a week.

Edgar had taught his manservant, Sumajeri, to make fresh homemade bread which he made every day in a mud oven. Every now and then Edgar was able to buy from neighbors a two-hundred-pound sack of oats to grind for porridge.

They enjoyed a lot of minor luxuries; Sumajeri used to bring morning tea before they woke up, accompanied by slices of bread and butter. But one day, after a particularly strenuous day Edgar had the misfortune to go back to sleep after Sumajeri had brought in his morning tea. He woke half an hour later to count seven rats sitting on his tray eating the bread and butter.

Ferguson and Edgar usually changed at the end of the day’s work and walked up together to the living hut with a hurricane lamp. They both liked a whisky sundowner and rationed themselves to one bottle a month, even though Scotch was only 12/6 a bottle.

As they opened the door the rats would run up the pole which supported the center of the room and disappear into the thatch. There was a standing order that no food should be put on the table before they arrived otherwise the rats won the race for it. Edgar generally had a go at them with his pistol and would hit quite a few. One evening however Ferguson went in first and the next thing Edgar knew Ferguson was jumping up and down clutching at his belt. A rat had run up inside his trouser leg and was finding the belt an obstacle. Edgar was quite helpless with laughter and collapsed in a chair. The rat finally jumped out of Ferguson’s open necked shirt.

One luxury that Edgar missed was the absence of a bathroom. They had the usual zinc tub into which hot water was poured from cans, but after a day’s heavy work in the fields on a cold evening it was a tremendous luxury to spend one night in town and to be able to lie down in a warm bathroom instead of having the upper part of one’s person completely frozen.

Another luxury that he missed was indoor sanitation. They constructed a convenience. In order to avoid smell and risk flooding during the rainy season, they dug a hole in a clump of trees about fifty yards down from the site of the house to a depth of sixteen feet. They built around it a wall of unburned brick with windows and an iron roof which served faithfully for many years. They covered over the hole with a wooden superstructure made of the local timber and thick floorboards. The only thing they had not bargained for was that from the underneath there was a serious attack by white ants. One day Edgar had a heavy-set friend from Salisbury visiting. Shortly after entering the convenience Edgar heard a loud shout of alarm and the visitor sprang out of the door looking very green about the gills. There had been an ominous crack and the entire contraption showed signs of collapsing into the sixteen-foot cavity!

All Ferguson said was, “You were nearly interred that time.”

So began one of the greatest friendships of Edgar’s life. Ferguson was much more than his farm associate. He was his closest and most reliable personal friend. They shared everything together. Edgar trusted him so completely in the management of the farm that it became possible for him to begin to realize his political career.

The historical novel Whitewashed Jacarandas and its sequel Full of Possibilities are both available on Amazon as paperbacks and eBooks.

These books are inspired by Diana's family's experiences in small town Southern Rhodesia after WWII.

Dr. Sunny Rubenstein and his Gentile wife, Mavourneen, along with various town characters lay bare the racial arrogance of the times, paternalistic idealism, Zionist fervor and anti-Semitism, the proper place of a wife, modernization versus hard-won ways of doing things, and treatment of endemic disease versus investment in public health. It's a roller coaster read.

References:

- By permission, sourced from Sir Edgar Whitehead's Unpublished Memoirs, Rhodes House, Bodleian Library, Oxford University.

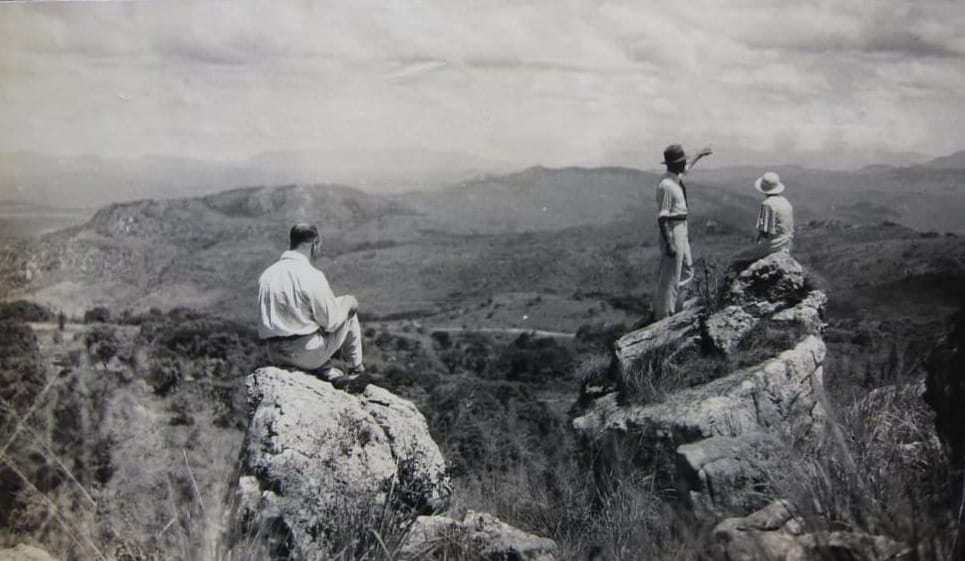

- Photo credit: By permission, Sir Edgar Whitehead's Unpublished Photograph Albums, Rhodes House, Bodleian Library, Oxford University.