No Water-borne Sewage, but Charming

Click here to in large.

No Water-borne Sewage, but Charming

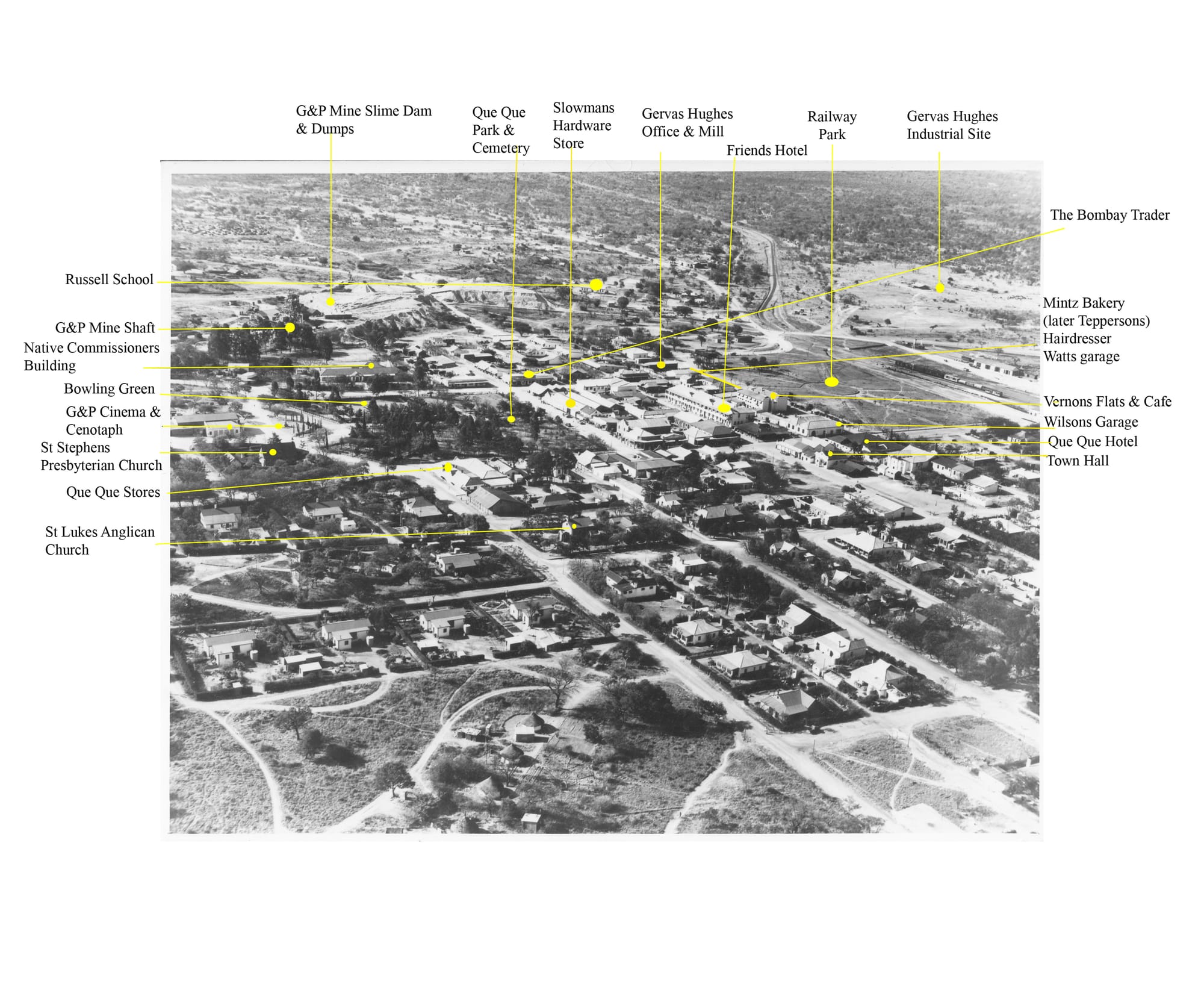

A number of readers have asked me where Gervas Hughes’ office and mill, and industrial site were situated, and fortuitously Peter Harris has come up with a wonderful aerial photo to give us the big picture then. Gervas’ photos show roughly made habitations scattered on the land, like the Old West in the nineteenth century. But by the early 1940’s, Que Que looks rather tidy – certainly from an aeroplane.

No Water-borne Sewage, but Charming

From the arrival of the Pioneer column in 1890 in Mashonaland until the Boer War ended in 1902, Southern Rhodesia (as it began to be called in 1894) was always in a parlous state. Expecting a ‘Second Rand’, after a dozen years ‘Southern Rhodesian stock stank in the noses of investors’. But then conditions began to improve. The new railway between Bulawayo and Salisbury was routed to serve the Globe and Phoenix Mine at the G&P railway station. The G&P really was a gold mine, even if small in comparison to the Rand mines.

Municipalities in Rhodesia had plenty of land, except Que Que, officially considered merely a civic appendage to the G & P. The Que Que area, recognized early on as highly mineralized, was widely pegged. Soon the village became hemmed in by mines on three sides and the Railway on the fourth. The gaps were subsequently taken up in major private land ownerships, it seems through political influence, by the legendary John Austen and also by Theo Haddon, for many years the general manager of the G&P Mine. British mining giant Lonrho holding a vast area of land and mining rights, was an obstinate impediment as well, for anyone with ambitions for the village.

But as can be seen in the photograph, probably taken in the early 1940’s (when Thornhill training base for WWII pilots was established in neighboring Gwelo), this confinement resulted in a pleasant village. There are plenty of trees, the houses are surprisingly ample and the roads, though unpaved, are properly made and kept. Motor cars look scarce. It was a picturesque place to get about on foot or by bicycle – it had atmosphere.

Unfortunately, the photo does not take in the village that belonged to the G&P on the left, which had even more charm. After WWII, Que Que burst its bonds. It built sprawling suburbs and industrial parks on the flat land to the east, where all the woodlands had long been cut down. The lovely mountain acacia clad hills and grassy glades to the west and south, between Que Que and Redcliff, the new village next to the new steel works, remained untouched.

Next week I’ll resume with Gervas Hughes’ saga.

Many thanks to Peter Harris of Durban for sharing the aerial photo from the Southern Rhodesian Archives. He was born in Que Que in 1936 His father, Richard, an Electrical and Mechanical Engineer, graduated from Faraday House College, London and immigrated in 1927. He worked on the G&P and Piper Moss Mines as well at the Tebekwe Mine in Selukwe, and Dandazi Mine near Bindura, before moving to Swaziland’s Havelock Mine, returning later to Rhodesia and the Turk Mine, owned by Meikles.

Thanks also to Tim Hughes, Andrew Kluckow & Abe Menashe for identifying landmarks and my husband Jan for photoshop entries.